Cristina Sánchez, looking back

“Silence is a way of telling things. The unwritten word is also eloquent. It’s said that shutting up is a form of lying, but I haven’t lied in these pages despite keeping quiet a lot. I’ve hidden parts of my life I’m still not able to relate; I’ve broadly drawn episodes and people that merit descriptions close to hyperrealism, but I’ve a gag in place that stops me from speaking.

“When I can liberate myself from this imposed silence, I will speak of the pain caused by the intolerance that doesn’t allow me to enjoy my profession as I could, the meanness of those that get in the way of my inhabiting a terrain conquered by men.

“Now is not the time - perhaps it is cowardice, but I don’t want to open up more fronts in my battle. I have to preserve my strength to defend myself: now is not the time to go on the attack. My silence is a way of leaving open the final pages of this history.”

So ended Cristina Sánchez’s first autobiography, ‘Matadora’, published in 1998 as she was about to start her second full European temporada as Spain’s most accomplished female matador. The book itself covered her life up until her reappearance at Nîmes - the site of her alternativa - one year after that historic event.

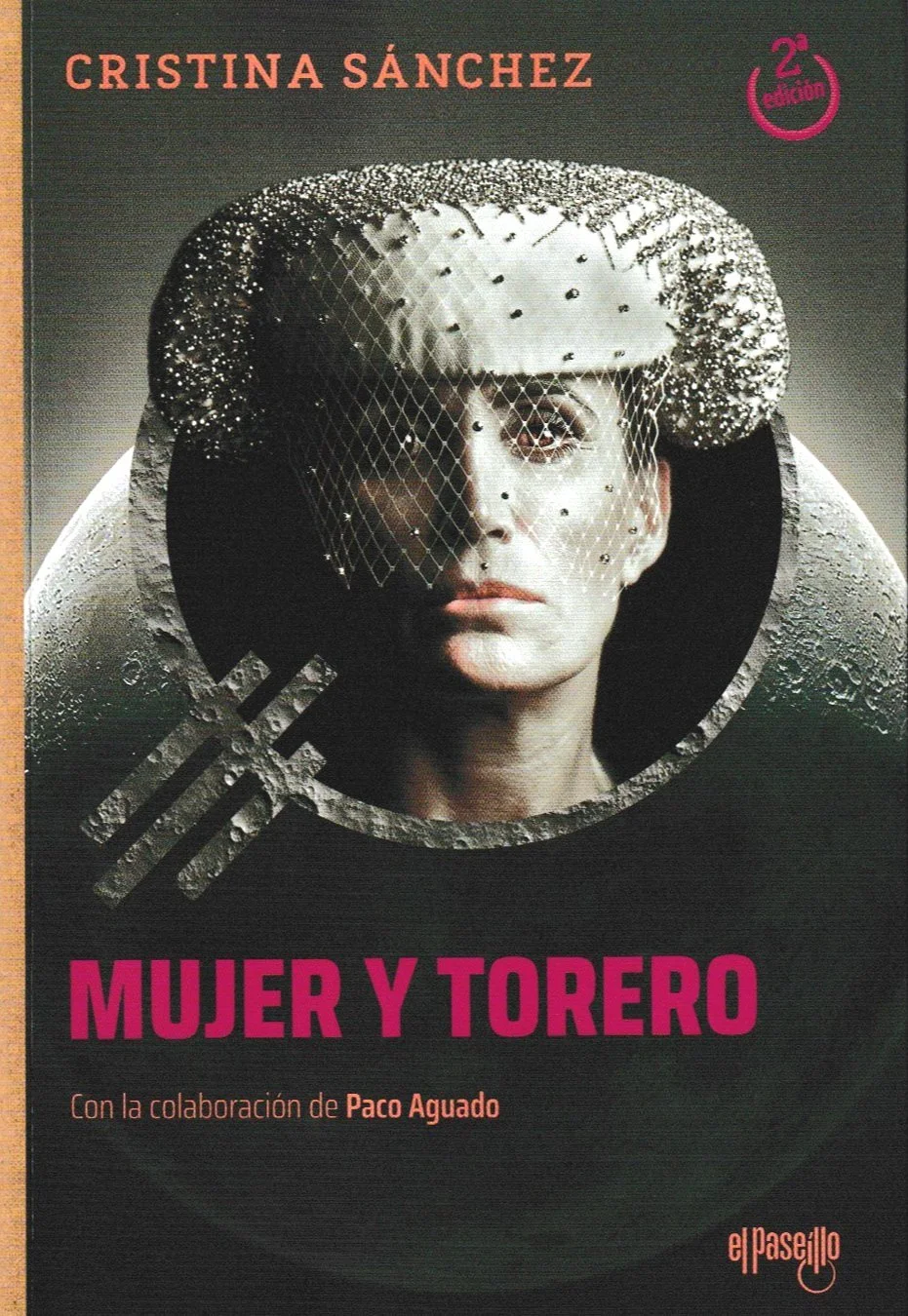

One might expect, then, that Cristina’s new autobiography, ‘Mujer y Torero’ would spill even more beans on her life in a predominantly male environment (she retired as a matador in 1999, returning briefly in 2006 and for a one-off corrida in 2016, but has had a long career as a bullfight commentator, as well as managing and mentoring toreros). Instead, the reader finds a mellower person looking back on her life as a woman and torero (note the order of the two descriptions), or perhaps someone who is now so deeply entrenched in the mundillo, she is even more wary of giving offence.

When she announced her sudden retirement in a press conference midway through the 1999 temporada, Cristina blamed her departure on the machismo of her fellow toreros, many of whom, she alleged, refused to appear on the same cartel as her. But, in ‘Mujer y Torero’ she states, “The problem is that there are people, especially in the generalist press and la prensa del corazón, who want to understand and explain things in the easiest possible way - by machismo […] But, in my case, that’s not how it was […] Although it’s true that some of the figuras didn’t like to have me beside them in the paseíllo, to be honest there weren’t many. […]

”Although some people have the strong idea that it was machismo that put a stop to my career, I must insist that I never saw things or felt that way. Although masculine in the main, el mundo del toro is what honestly gave me a place in it, believed in me and has respected me as a woman from when I was 14 years old to nowadays when I no longer wear the suit of lights.”

She now regards that press conference as a misstep and says instead that her retirement was caused by her lack of eagerness to continue toreando. Whether this was the result of anxiety or depression, she remains unclear: only that, four days earlier in a corrida at El Molar, she kept asking herself what was she doing there and couldn’t wait for the festejo to be over and to discard her traje de luces.

Her manager, Simon Casas, treated relatively kindly in ‘Mujer y Torero’ (although she does point out his interest in her waned as he took on two new charges - the veteran Ortega Cano and the novillero Alberto Ramírez), later claimed that Cristina lacked the strength needed to execute the suerte de matar successfully. Whilst acknowledging she had a weakness with the sword, Cristina sees things differently: “Going in for the kill, everything in my head worsened. Truly, I believe I was never able to overcome this, knowing for certain that the secret of killing bulls well has nothing to do with strength. If people only knew how little is involved in placing the sword if the phases of the suerte are done well and you hit the right spot! […] Everything comes down to one’s technical skill and having confidence in yourself at such a critical moment […] Despite training in it a thousand and one times - much more than any other suerte - I never got the hang of it […] At no point in my career did I come across the formula for going in to kill with sufficient decision.”

Held up by some as a feminist model during her time as a torero, Cristina is revealed in the book as being no sister. Women, she says, were amongst her fiercest critics. “I believe that […] on too many occasions women are, between ourselves, our greatest enemies, myself included. The competitiveness we carry inside means we show little solidarity or team spirit in our work […] I’ve always preferred to be with men - whether it’s in business or sharing time together or even arguing about things, men have much more nobleza than women.”

A woman she criticises is fellow matador Mari Paz Vega. Although Cristina agreed to be her alternativa ‘padrino’, it appears the two never got on. Cristina had a strong wish to compete on equal terms with male matadors; she didn’t like to be referred to as a ‘torera’ or (despite that first book’s title) ‘matadora’; and she generally avoided appearing on all-female carteles, rightly considering the history of such carteles to be exploitative and frivolous. Mari Paz, says Cristina, never understood this approach, to the extent that she regarded Cristina’s general lack of interest in appearing with her as a form of boycott. As Cristina puts it: “Mari Paz and I pursued our careers in very different ways, just as our forms of understanding our profession were different too. I don’t know which of the two approaches was best, but I do know they were different in every sense and I never identified myself very much with her way of doing things.”

In ‘Mujer y Torero’, Cristina gives her views on more recent women hoping to become matadors. She managed the salmantina Raquel Sánchez [incorrectly named - see Comments below] for a short while: “I’ve a concept of the profession, perhaps a wrong one, that she never understood […] I treated her as one more torero and insisted that women had to make even more effort if they wanted to make a name for themselves in the bullrings, just as I did. But, in the absence of greater involvement, I ended up being disappointed.” Carla Otero she regards as a dedicated torero with an extraordinary level of afición, but set back by a bad goring of a couple of years ago. Of Olga Casado, she says, “She was really good in the Vistalegre festival for the Valencia flood victims […] She can be a very good catalyst at this moment in time, as long as, in my personal opinion, she doesn't stray from the good guidelines of bullfighting. It’s about respecting the classical laws, without relying on exceptions or making mistakes by looking for shortcuts to avoid competition on equal terms with men. It’s her turn - as occurred with me and my predecessors - to surpass me, purely due to the evolution of toreo. And I hope she succeeds.”

Although no longer an active bullfighter, Cristina still regards herself as both a woman and a torero - sometimes almost to the point of having a split personality. She sees her decisions to make a one-off reappearance at Cuenca in 2016 to perform in front of her sons; to participate in the celebrity TV shows ‘La Granja’ and ‘Expedición Imposible’; to establish a fashion company (a venture that didn’t survive the 2008 economic crash); and to accept Antonio Ferrera’s invitation for her to act as his apoderado as examples of the risk-taking and lack of conformity that led her to become a torero.

“Everything I’ve learnt with this unique animal [the toro bravo] has helped me since to take the most important decisions and become the person I am today - Cristina Sánchez the woman, wife, mother, friend… If I didn’t have this framework, I’m sure that my life now would be much smaller. I would have stayed in Parla, got married, worked for a small salary and needed to save a lot to buy a 70 sq metre flat, just like millions of women. But toreo gave me a much bigger outlook, a status that made me feel better as well as completely fulfilled for not having settled for the normal way of things.”