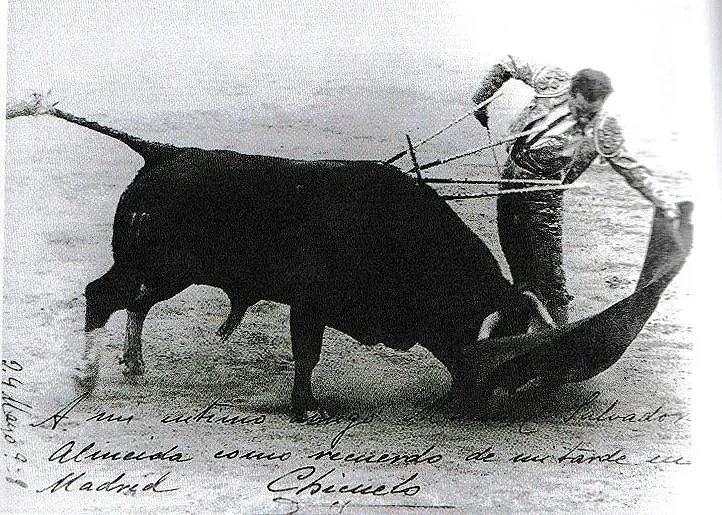

Pre-dating ‘Corchaíto’

Chicuelo toreando ‘Corchaíto’

“Chicuelo’s left hand, set to the register of the pase natural, which he’d been trying to achieve for so long without success until this afternoon, has linked four passes.

“- One. - Two. -Three. - Four.

“[…] The pase de pecho doesn’t follow: instead, two more naturales. The successful pase natural! With another such, the spectators get to their feet and acclaim the torero. Without the left hand, no faena achieves its summit.

“The faena enters a new phase, the two hands alternating. The passes merge into one another, the high with the low, the effective pass controlling the bull with the adorno, occasionally an afarolado. Once, in a pase ayudado, the muleta is held at the end and the torero turns his body, a reminder of the chicuelina, reproducing the cape pass with the muleta. And before this gigantic faena finishes, the left hand signs off with three pases naturales, the most amazing of all, because, with the bull worn out, the artista has had to push the boundaries further and pull on the centre of the palillo with greater firmness.”

So reads Clarito’s famous report in El Liberal of Manuel Jiménez Chicuelo’s faena with the Graciliano Pérez Tabernero bull ‘Corchaíto’ in Madrid’s bullring on May 24 1928 - the faena that is said to have created the modern approach towards linked toreo.

Prior to Chicuelo’s breakthrough, the norm was to torear ‘en ochos’, always toreando to the bull’s furthest horn and linking a derechazo or natural with a pase de pecho. Despite his new positioning, this approach was maintained by Belmonte, and also formed the usual basis of Joselito’s toreo despite the maestro’s occasional sallies into the beginnings of linked toreo as we now know it.

A new biography of Chicuelo, Manuel Escalona Franco’s ‘¡Chicuelo! El hombre que cambió el toreo’ makes it clear, however, by reproducing contemporary reports, that May 24 1928 wasn’t the first occasion on which the sevillano emphasised the linking of passes with the muleta. Can we believe these reports, made during a period when the bribing of reporters was commonplace? Escalona says yes, for Chicuelo’s manager, his uncle and ex-banderillero Eduardo Borrego Zocato, had a reputation for steering clear of such practices.

Chicuelo took the alternativa from the hands of Juan Belmonte on September 28 1919 during Sevilla’s Feria de San Miguel and even then the 17-year-old showed signs of what was to come, Don Criterio in El Liberal noting that, at one point, the new matador “changed the cloth hand and gave three naturales, estupendísimos, and a pass from on his knees,” while the critic of the Spanish taurine publication The Times, summarised the same performance as “a faena of linked naturales, the body held straight, toreando solely with the arms, and a great and regal estocada.”

On his best days the natural successor to Joselito, Manuel Jiménez excelled in toreando with the left hand. In 1920, some months after Joselito’s fatal goring, Don Pío wrote of Chicuelo in La Libertad: “We can console ourselves knowing that toreo al natural, which would appear to be proscribed by the modern escuela rondeña of the right, hasn’t perished with Joselito, but is alive, vigorous, strong and beautiful, with ‘his son’. Long live toreo with the left hand! Long live the emperor!”

The first reported occurrence of Chicuelo’s extended series of linked naturales appears in September of that year at Valladolid, El Timbalero writing in El Adelanto, “he performed five, six, seven (who knows how many!) pases naturales before giving a very pretty chest pass.” It was a terrific afternoon, the matador cutting two ears and a tail from each of his bulls and circling the ring twice after each lidia. A year later, on September 25 in Barcelona, Chicuelo brought off another long series, Serrano Azares noting in El Diluvio, “Chicuelo went to the bull on his own, the muleta extended in his left hand as is no longer customary in modern bullfighting, may Allah confuse… With his feet still, nailed in place, his figure upright and turning slightly in time with the movement of the muleta, he executed five pases naturales, cheered in unison with many other tremendous ‘Olés!’” Sevilla’s La Maestranza was witness to the miracle once again on October 12 1924 at the city’s traditional festejo to benefit la Cruz Roja, Triquitraque recording in El Correo de Andalucía: “Chicuelo moved the muleta slightly and the bull charged forward… Impassive and with an inimitable gracefulness, Chicuelo ran the hand and gave a natural pass, and then another, and then another, and then another… Four superb linked naturales, of incredible beauty! Four natural passes, impossible to describe!”

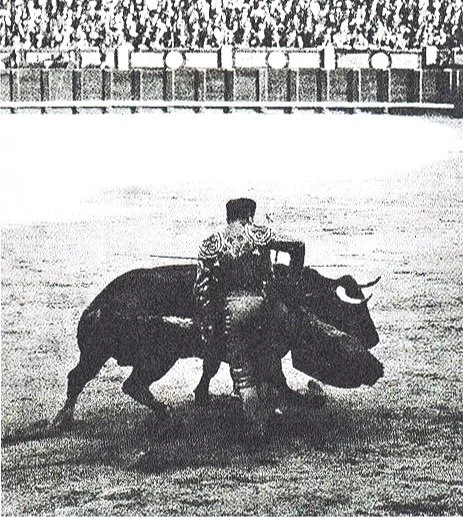

Chicuelo with ‘Dentista’ in la Plaza El Toreo de la Condesa, Mexico City, October 25 1925

Chicuelo was a revered matador de toros in Mexico, where he first performed in the country’s 1924/25 temporada. On February 1 1925, he triumphed at the Plaza El Toreo de la Condesa with a bull of San Mateo, Curro Castañares commenting in Muchas Gracias: “The great thing, the most extraordinary, was the constant use of the left hand in his torerísmo approach, which culminated with the first bull, which he dispatched with unequalled clasicismo. Five pases naturales in succession (like Gallito). Then, another two naturales linked with a chest pass (like Belmonte).” The critic of El Sol described the performance as the faena of the temporada and then went further: “It’s been years since we saw anything like this. I don’t know if Lagartijo el Grande, Guerrita or Montes and Curro Cúchares would do anything more than what I saw Chicuelo achieve yesterday with his first bull, but even if they had done, I could never believe it.”

On October 25 1925, in the same plaza and with the same ganadería, even this performance was surpassed. With the bull ‘Dentista’, Chicuelo produced no less than 25 naturales in linked series. Rafael Solana Verduguillo reported in Toros y Deportes: “When Chicuelo, without dedicating to anyone, went out to contend with ‘Dentista’, there was terrific commotion in the plaza. Everyone knew that the maestro was going to perform one of the great faenas, but it didn’t cross our minds that it could become what our eyes had the privilege of seeing. The initial muletazo was a natural with the left hand, followed by another natural, impressive for the temple and bravery displayed, and then another, the bull brushing his waist. By now, everyone was on their feet. It was impossible to follow the faena step by step as your chronicler forgot his obligation to record the details on his notepad and, throwing paper and pencil to one side, focused on enjoying the spectacle in all its grandeur […] What occurred was much arte, much bravery and much esencia torera. There were TWENTY-FIVE PASES NATURALES, all of them classically formed and completed, provoked by the pierna contraria, permitting the bull’s horns to almost touch the lidiador’s stomach and, at that moment turning its head aside while the rest of the bull’s body continued its natural path and went past brushing the chaquetilla’s alamares.” Although Chicuelo needed three attempts to kill ‘Dentista’, he was awarded the ears and tail and was carried out of the plaza to his car. Writing of the same performance, but now in the weekly La Corrida, Verduguillo said, “If the Madrid reporters who, at all costs, try to downplay the merits of this torero and to belittle his efforts had seen him this afternoon, they would have had to recognise that they are knowingly making fools of themselves, or that they don't even have that much […] professional decency.”

Further excellent faenas based on series of linked passes occurred, for instance at Figueras and Granada in 1925, but Madrid’s reporters would have to wait until that 1928 faena to ‘Corchaíto’ before the scales fell from their eyes. And it was their enthusiastic coverage (an appendix in Escalona’s book contains no less than 16 accounts of Chicuelo’s performance that afternoon), and the fact that the faena occurred in Spain’s premier plaza, that established the myth that it was on that afternoon when Chicuelo first established the importance of linking passes.

Chicuelo gives a pase de la firma to ‘Corchaíto’

Manuel Jiménez Chicuelo is nowadays rightfully seen as a crucial part of the chain that represents the evolution of the toreo of Joselito and Belmonte to the toreo we enjoy today. For English-speaking aficionados, the trianero was poorly served by Ernest Hemingway, who was dismissive of the matador, finding him physically unattractive, describing him and his toreo in disparaging feminine terms, and calling him “cowardly” as a result of his first goring (at Barcelona in 1929). Certainly, like a lot of artistas, Chicuelo was an irregular torero throughout his career, and it appears that Hemingway witnessed some of his poorer performances. Spanish writers have taken a broader view. Pepe Alameda recorded Manolete telling him that his own toreo was based on the torero maintaining his position as long as possible “en su centro, en la línea”, and that the best matador he’d seen doing this was his padrino, Chicuelo. Alameda himself wrote that, while Guerrita had invented the possibility of toreo en redondo and Joselito had managed some linking of passes, it was Chicuelo whose graceful and extended toreo en redondo gave the faena the prominence it has today. Nestor Luján acclaimed Chicuelo as “the creator of the rhythm of modern toreo, the faenas of smooth and fluid linking.” Carlos Abella has written, “Chicuelo is the initiation of a line that gave rise to an excellent category of toreros, continued through Pepe Luis Vázquez, recreated by Pepín Martín Vázquez and Manolo González, and cristalized in the sublime taurine magic of Curro Romero and, more recently, of Julio Aparicio and Morante de la Puebla.” Manuel Escalona’s new biography of Chicuelo, written with the co-operation of the matador’s descendants, certainly does this important torero justice.